Contact Info

Ryan K. McNutt, Ph.D.

- rmcnutt@georgiasouthern.edu

- 478-982-1660 (state park)

-

facebook.com/camplawton/

twitter.com/CampLawtonGSU

We are lucky to have several descendants of prisoners and guards from Camp Lawton who are dedicated to sharing their histories with us. Through their willingness to share family stories, journals, artifacts, and images, we are able to learn about some of those people who lived at Camp Lawton, on both sides of the stockade. Their stories hint at the wide variety of backgrounds and experiences of those in the camp. We hope that these pages will also encourage other people to tell us about their family histories, and we would love to add their information to these pages.

Nina Raeth: Sebastian Glamser

(Great-Grandfather of Nina J. Raeth)

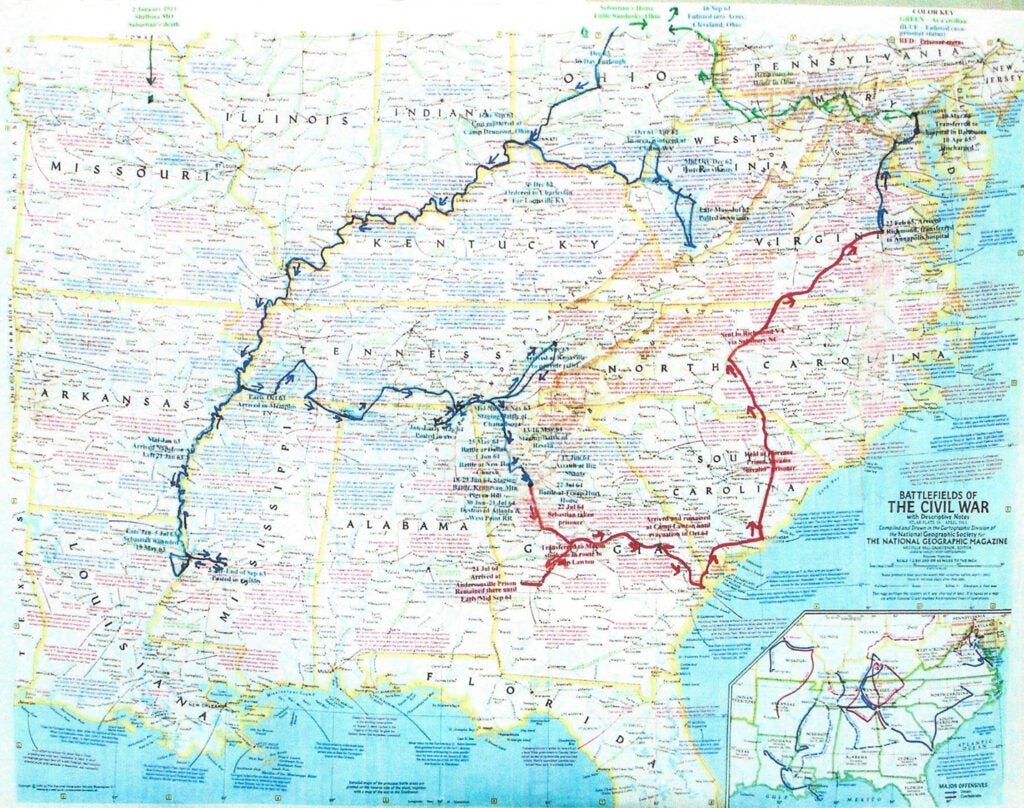

Sebastian Glamser was born January 20, 1834, in Jungingen, (Hohenzollern) Germany. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1854 at the age of 20, probably coming in through Philadelphia PA since he mentioned in his Claimant’s Affidavit for Pension that he lived there prior to moving near Little Sandusky, Ohio. He stated he had lived there for approximately seven years as a farmer before entering into the Union Army. He joined Company F, 37th Regiment of the Ohio Infantry Volunteers at Cleveland, Ohio.

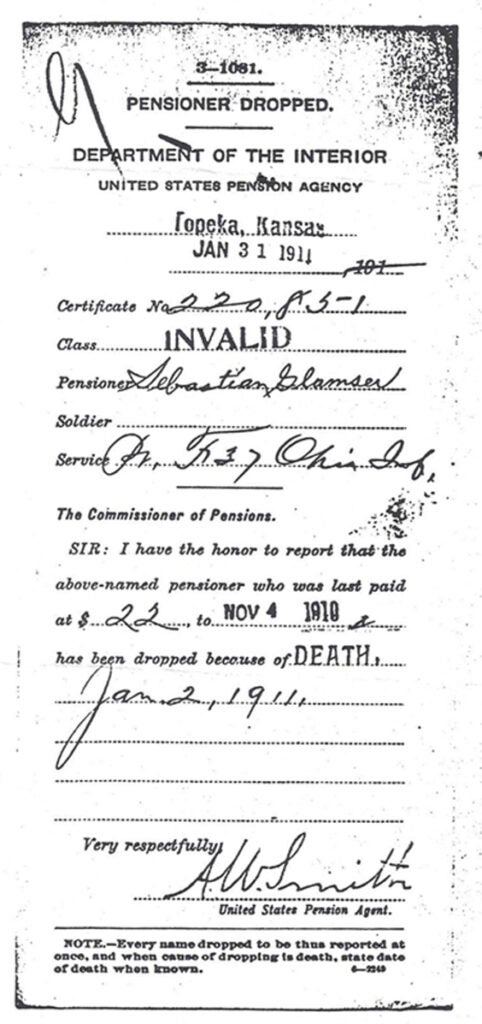

In Sebastian’s pension claim, he stated that he was claiming pension for:

“Bronchitis and Asthma. Said disability was incurred in the month of February 1865 and was caused by exposure to stormy and cold weather on the road from Florence SC to Richmond, Virginia and exposure and hard fare while in rebel prisons, Andersonville, Milledgeville [sic, Millen], Macon and Florence.”

In his affidavit, he states:

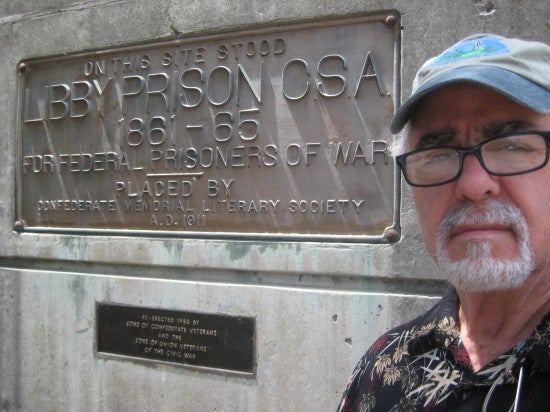

“I was captured on the 22nd of July 1864 near Atlanta GA. Was taken from there to Andersonville prison. And confined in Sumter (Camp Sumter was original name) prison for some time. From there we were taken out for exchange, but for some reason was not exchanged. But were taken to Macon GA. And kept there till some time. Were taken from there to Millen GA and confined there some time. Were taken from there to Florence SC, and remained there in Stockade till about the middle of February 1865. I was then taken out and sent to Richmond VA. All my comrades of my co. and Regt were left behind in Florence and I have not seen or heard from any of them since. And if any of them are alive I do not know of their whereabouts at this time. On the trip from Florence SC we were frequently ambushed and had to lye (lie) out without any shelter or fire with poor clothing. The weather was very cold. And while lying at Danville many of the prisoners froze to death. From the exposure of my imprisonment and especially on the trip from Florence to Richmond, I contracted a breathing (?) trouble which has since developed into asthma and bronchitis. On our arrival in Richmond we were confined in Libby Prison. Was there paroled and sent inside the Union line. Sometime in the latter part of February 1865 and taken to hospital at Annapolis MD and treated by hospital surgeon. Was removed from there to Baltimore MD and placed in hospital for treatment some time. Remained till discharge on Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability and expiration of time of service. Discharge date April 10th, 1865.”

I am certain that Sebastian served in the Prussian Army before he was granted permission to immigrate to this country. Military service was mandatory for young Prussian (German) men during the middle 1800s. That would easily explain why he was 20-years old at the time he arrived in the United States. He was the only son who risked the month-long or more journey crossing the Atlantic Ocean. His sister, who was younger, had been the very first of his siblings to come to America. From family history I learned that Sebastian and his sister were saving money for another brother to come over, but they lost a brother in a drowning accident on the Bodensee (Lake Constance) when all hands and passengers went down with the ship. Thus, no other brothers wished to take that risk to come to the New World.

Sebastian’s regiment covered an amazing amount of territory, especially when much of it was on foot, or via steamboats, during the Civil War. The unit was mustered in Camp Denison (Cincinnati) Ohio and soon moved into the Kanawha Valley, what is now part of West Virginia. After fifteen months, they were ordered to head for Vicksburg, Mississippi, by steamships down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. The 37th was deeply involved in activities before and during the Battle and Siege of Vicksburg and that is where Sebastian received his one and only wound of the war—a bullet grazing his right temple, something for which he never even received medical attention. That occurred May 19, 1863. The unit remained in the Vicksburg and Jackson areas throughout the summer, but they eventually received orders to go back up river to Memphis and make their way to Chattanooga as quickly as they could get there. November 25, 1863, found the unit in fierce battle on top of Tunnel Hill on Missionary Ridge, during the Battle of Chattanooga. After that resounding victory, they were diverted to Knoxville, only to find out upon arrival that Burnside’s men were not in the dire straits that Sherman was lead to believe. Thus, the men returned to the Chattanooga area where the men who had re-enlisted were given a 30-day furlough to return home while the others remained in the vicinity. Upon the return of those men lucky enough to get home for a brief stay, the troops began their march for Atlanta. Their fighting began in Resaca, Georgia, and on down to Dallas, New Hope Church, Allatoona Hills, and on to Kennesaw Mountain where the regiment was in a nightmare of a battle at the base of Pigeon Hill on June 27, 1864. After that disappointing defeat, the unit began to make their way to Stone Mountain, but were diverted to Decatur, where they marched into Atlanta days later, marching throughout the night to get in place on July 22, 1864. The 37th was in battle once again surrounding the area of the Troup Hurt House where Sebastian and other comrades where taken prisoner. They had less than a quarter of a mile to have to march to reach the train that would bring them to Andersonville Prison, arriving at that hellish stockade on July 24, 1864. Because of the resounding Union victory in Atlanta, he fortunately did not stay in that godforsaken prison for more than six or seven weeks. Since the Confederates feared that Sherman’s troops would come to free the prisoners, that prison was evacuated in September 1864. We know that the healthy prisoners were all removed by September 17, 1864, and Sebastian was transferred to a prison pen in Macon, Georgia, until Camp Lawton, near Millen, opened to take the prisoners beginning October 10. When it was determined that Sherman’s “March to the Sea” was under way and heading for Camp Lawton, that prison was quickly evacuated. Sebastian ended up going to Florence, South Carolina, via Savannah and Charleston. (Keep in mind that this was during the fall and winter of 1864/65, one of the coldest winters on record.) From Florence, Sebastian was heading for Richmond, going through Salisbury, North Carolina, and Danville, Virginia, before arriving at Libby Prison. Around February 22, 1865, now 31-years old, Sebastian was sick from bronchitis, rheumatism, and possibly pneumonia due to laying out nights as the trains would stop for the night. There were no fires and no blankets either for warmth. The prisoners laid out with only the rags of their uniforms to keep them warm. Sebastian witnessed prisoners freezing to death during that journey. He was considered an “invalid” prisoner and paroled back to Union lines where he was immediately sent off to a hospital in Annapolis, Maryland, for several weeks and later to a hospital in Baltimore. He was discharged on April 10, 1865, and made his way back home to Little Sandusky, Ohio. Upon his arrival, his brother-in-law stated that Sebastian was so ill he had to have assistance to get into the house.

Sebastian recovered, but not nearly back to the healthy stature of the man he was before going off to war, and in February 1867 he married Elizabeth (Eliza) Mahley. They began their journey west as well as their family, making it as far as Itasca, Kansas, before they turned back to the eastern half of the state. He and his wife had 10 children, and all lived a full life. Their seventh child was my grandmother. Sebastian and Eliza eventually moved to Shelbina, Missouri, where they lived out their lives on a farm just south of town. Eliza passed away about four years before Sebastian; he was three weeks short of turning 77 when he died in January 1911.

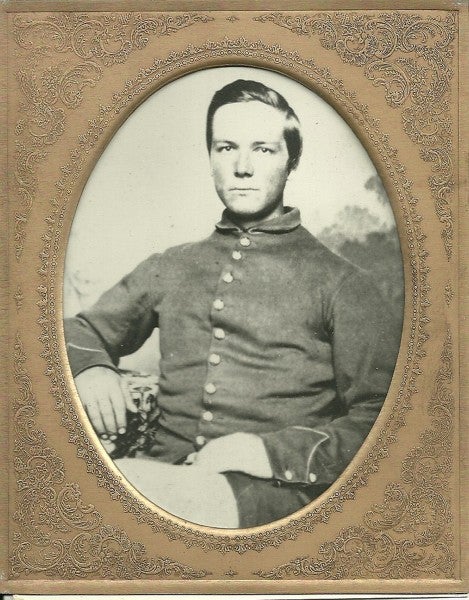

Doug Carter: Jesse Taliaferro Carter

My great grandfather, Jesse Taliaferro Carter, was born in Warren County Georgia on August 26, 1846 to Wiley Carter Sr. and Ann Ansley. Jesse’s mother died when he was a very young child and his father then married Sarah Wilson, a widow. In 1851 Wiley moved his family to Schley County where he became a successful planter with a plantation containing 2400 acres in both Schley and Sumter counties. Soon after the war began, two of Jesse’s older brothers, Wiley Carter Jr and Littleberry Walker Carter, great grandfather of President Jimmy Carter, joined the Sumter Flying Artillery which was assigned to the Army of Northern Virginia.

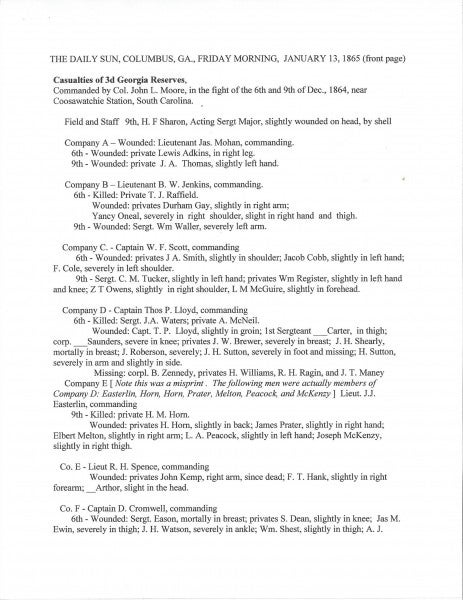

Jesse’s father died on March 4, 1864. A few months later, seventeen year old Jesse enlisted as a private in Company F, Third Georgia Reserves. He brought his percussion fowling piece shotgun with him when he enlisted. Initially, he served as a guard at Andersonville, which was located approximately 20 miles from his home. When Camp Lawton was opened, Jesse and his unit served as guards there. When Camp Lawton closed after only six weeks, Jesse and the Third Georgia Reserves joined other Confederate forces at Coosawhatchie, South Carolina, defending the railroad which ran from Savannah to Charleston. From December 6 to December 9, 1864, the Confederate forces fought a Union force which was composed of units from the Union Army, United States Colored Troops, Naval Infantry, and the United States Marine Corps. The Confederates prevailed and prevented the Union force from cutting the railroad. The Third Georgia Reserves suffered numerous casualties during this engagement, including Jesse who was slightly wounded in the neck on December 6th. On Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865, Jesse and his unit fought in one of the last engagements of the war, the Battle of Columbus, Georgia.

After the war, Jesse returned to Schley County, where he farmed. By 1870, he was married to Nancy “Nan” Jane Spivey and had a young child. Jesse and Nan raised six children. Shortly after the birth of their last child, Nan died. On October 1, 1899 Jesse married Susan Ann Augustus “Gussie” Jones. By 1910, he had moved his family to Richland in Stewart County, Georgia, and had become the owner of a small grocery/general store. Jesse and Gussie’s marriage produced two children: a daughter, Bobbie, and a son, William. My grandfather, William Jackson Carter, was born December 16, 1901.

As an adult, my grandfather wrote the following about his father Jesse:

“My dad had a horse and buggy and even when the automobile came he stuck to his favorite mode of transportation and had no use for the new contraption which scared his horse and thus added to his hope that the newfangled plaything would soon be forgotten. Old Minnie was smart and could take us to our favorite fishing spot and home again even on the darkest night and loved the long walk to Ponder’s Mill, our favorite swimming hole where Papa would take us on Sundays. We did not have a saddle but a croker sack (burlap bag) served pretty well for a bumpy ride on Minnie’s back. Papa was pretty old, 55, when I came along, and had very little except our home, a small grocery store, and Minnie and the buggy.”

Jesse died in Richland on February 27, 1924 from “uremic poisoning” and is buried beside “Gussie” at Harmony Cemetery in Richland. His brother, Wiley Carter Jr, a seriously wounded veteran of the Sumter Flying Artillery, also rests at Harmony. Jesse’s fowling piece which he carried throughout the war is on display at the Georgia Southern University Museum.

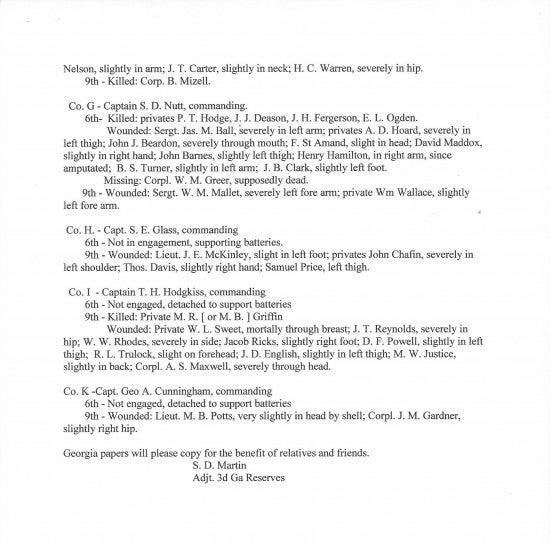

THIRD GEORGIA RESERVES

Below is a transcription of a newspaper article listing the casualties of the Third Georgia Reserves which occurred during fighting on the 6th & 9th of December 1864 near Coosawhatchie, South Carolina. The article appeared on the front page of the Jan 13, 1865 issue of “The Daily Sun” newspaper published in Columbus, Georgia. I obtained microfilm of the newspaper from the University of Georgia Main Library in Athens. The Third Georgia Reserves and the First Georgia Reserves, who had also served at Camp Lawton, were part of the Confederate forces which successfully defended the railroad which ran between Savannah and Charleston from being cut by the Union forces.

Larry Knight: Adelbert Knight

Adelbert Knight

Private/Color Guard

Company “F”

11th US Infantry

1862-1965

GAR Post No 42, Belfast, Maine

Adelbert Knight was one of nine children born to Abner and Julia Ann Fletcher Knight in Lincolnville, Maine on January 16, 1841. Unfortunately, four of Adelbert’s siblings died at or under the age of 21. One of his two older brothers, Jonathan (a Private with the 4th Maine Volunteer Regiment) died at age 23 after being captured during the Battle of First Bull Run (a.k.a., First Manassas), only 34 days after enlisting. He was imprisoned at several locations in Virginia, Alabama and North Carolina, for a total of about 312 days. Ten days after being paroled due to illness, he lost his personal battle with scurvy at City Hospital on Blackwell Island (now Roosevelt Island) in the East River of New York City on July 6, 1862. He was buried in Cypress Hills National Cemetery in Brooklyn, NY, with a memorial to him on the back of his parents’ gravestone in Lincolnville, Maine. His oldest brother, Augustus, lived in Montana, where he was mining for gold, and avoided the war. At this time, there has been no indication (back in 1862 or now) whether any of the Knight family knew of Jonathan’s ordeals, as the Adjunct General’s Reports noted that Jonathan was killed during the First Battle of Bull Run.

Adelbert enlisted in Portland, Maine at age 21 on March 26, 1862, as a Private in the 11th US Infantry, Co. F, 1st Battalion (approximately 2 months before his brother’s death). However, he only started writing in his diary on December 11, 1862. In April 1864, he was promoted to Color Guard for his Regiment. During this time of the War and where his Regiment was located, there were few battles and Adelbert found the time (in addition to writing letters) to transcribe his first diary into a second one, allowing him to send the first diary home (with a letter written in the diary) to his mother, in addition to other personal items not required (e.g., winter clothes), as well as other things (aka, “trinkets”, “souvenirs”, etc.) that he found after the battles in which he had been engaged.

From online records, the 11th US infantry fought in about 20 major battles, and Adelbert fought in 17 of them, including , Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg and Wilderness, before being captured during the Battle of Cold Harbor, outside Richmond, VA on June 2, 1864. He notes that approximately 45 men from his regiment were captured, with a total capture of 600 Union soldiers that day.

Adelbert entered and was detained in Libby Prison in Richmond on June 3, 1864. He was confined in a tobacco warehouse that held 250 prisoners on the floor he was assigned. He left Libby Prison six days later by train on June 8th and headed south to Georgia.

On June 14, 1864, Adelbert arrived in a small community (approximately 600 miles south of Richmond, VA and 125 miles south of Atlanta) called Andersonville, GA, where Camp Sumter (aka, Andersonville Prison) was located. The following day, after a relatively short walk, he entered the prison’s stockade area of approximately 16.5 acres. Food and consumable water were scarce and, to survive, decided to sell his ink and pen for bread, only ten days after arriving at Andersonville. It appears that he tried using other ink products (“homemade” possibly), but decided to use lead (from pencils or bullet shrapnel), as the ink(s) he tried using soaked through the pages of his diary. He continued to keep writing in his diary until his last entry on February 20, 1865. Over the years, the lead-written writing became difficult to read at times. This became a challenge when I transcribed the diary in 1970 for a high school class project.

His daily diary entries were short but to the point. He describes the weather, the rations he received, the soldiers who were severely ill or died; and the “news” (i.e. rumors usually) going around about the war as well as the prison he was in, some true and some false. With rations being minimal, there was food available for a price, such as molasses ($12.00/gallon), eggs ($1.00 each), potatoes ($1.50/dozen) and onions ($0.25-$1.25/each).

During his incarceration, Adelbert worked on expanding the stockade area from 16 acres to 26.5 acres. When he arrived on June 15th, there was a ratio of one (1) acre for every 1,255 prisoners. As he left on September 28, 1864 for Savannah, the ratio decreased to 386 prisoners to every acre inside the stockade. This was due in part to the increased stockade area, but also from prisoner movement to other prisons (for exchange or hospitalization), prisoners changing their allegiance to the Confederate side, as well from death due to sickness and disease. Such deaths were caused by conditions such as lack of acceptable shelter (if any) during the hot and cold weather months, poor health and hygiene, and malnutrition. The National Park Service identified some of the reasons for the high death rate at Andersonville to be from abscess, anasarca, ascites, asphyxia, catarrh, constipation, diarrhea, diphtheria, dysentery, enteritis, erysipelas, gastritis, hemorrhoids, hepatitis, hydrocele, icterus, laryngitis, nephritis, pleurisy, rubeola (measles), scurvy, smallpox, tonsillitis, typhoid and ulcus.

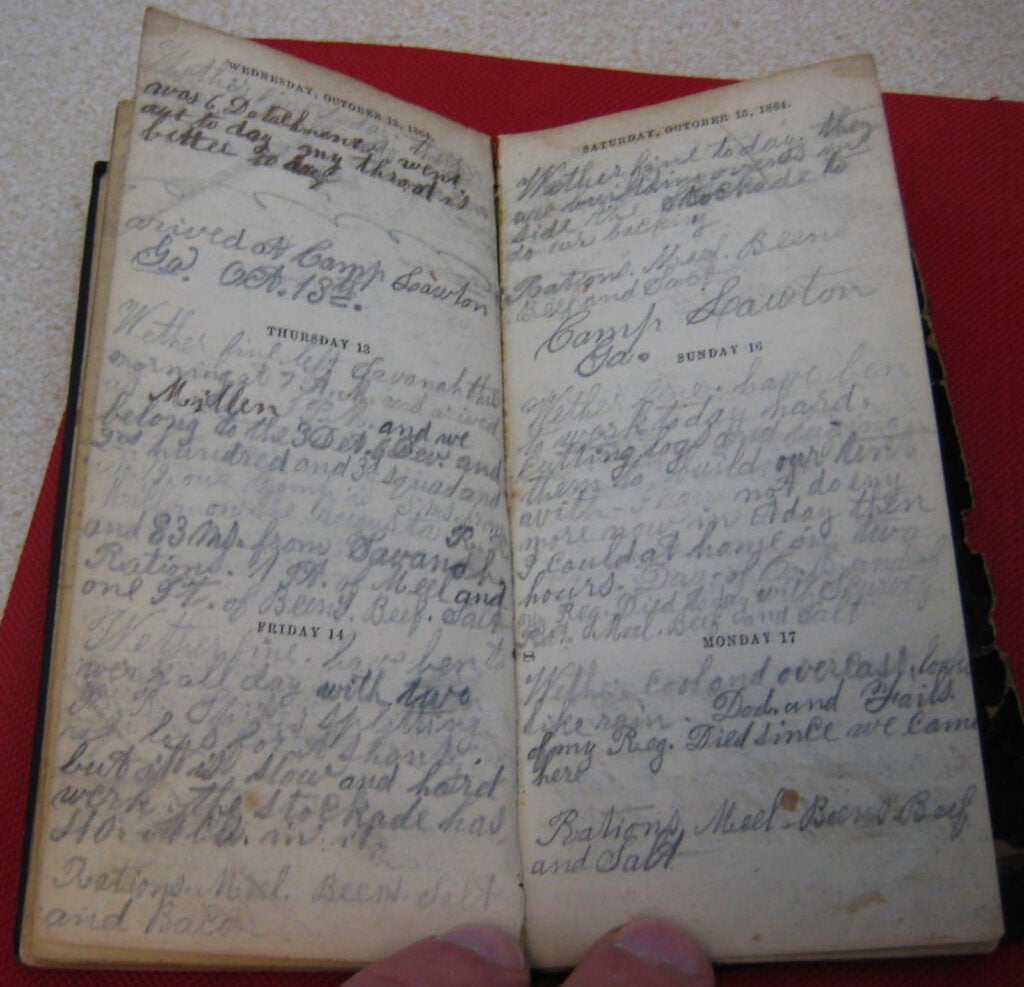

On September 28, 1864, after imprisoned for 106 days in Andersonville, Adelbert left by railcar for Savannah, where he stayed for 14 days. He entered Camp Lawton in Millen, GA on October 13, 1864, which was approximately 83 miles northwest of Savannah. He wrote in his diary the day he arrived:

“Wether fine left Savanah this morning at 7a.m. and arrived at Millen 1 p.m. and we belong to the 3 Det, 6 Div. and 2nd hundred and 3d squad and No. 19 our Camp is 5 ms from Millen on the Augusta R.R. and 83 ms from Savanah. Rations. 1 pt. of Meel and one Pt. Beans. Beef. Salt”.

The prisoners used railroad spikes to split logs for shanties (and were possibly used for constructing the stockade walls as well). Within a few days of arriving at Camp Lawton, several soldiers of his regiment died (some due to scurvy, which Adelbert started to contract due to poor rations probably). Rumors continued to spread about possible exchange, but it never occurred until the following year for him.

On the second day at Camp Lawton he mentioned “The stockade has 40 men in it” and the third day noted “building ovens inside the stockade to do our backing” (i.e. baking).

Adelbert did considerable manual labor, as his diary mentions for October 16, 1864:

“Wether fine. Have been to work to day hard. Cutting logs and luging them to build our tent with. I can not do any more now in A day then I could at home in two hours.”

There was considerable “chatter” about exchanges of prisoners, but more and more prisoners were arriving at the same time (with no shelter for them, but plenty of money for gambling).

There was an Election on November 8, with Abe Seincock getting the majority of the votes (834). The following day prisoners were inspected to determine the most in need of clothing. Per Adelbert’s diary, on November 14th, doctors inspected the sick for potential of a future exchange. At this time food could be purchased, such as $0.25 per Qt. of Meel or Beens, $0.25 per pint of rice, $2.00 per quart; and one bushel of sweet potatoes for $40.00 in Confederate money or $8.00 in Green Backs. Rations that day consisted of one gill (half cup) of rice, about one quart of sweet potatoes and 5 oz. of Beef and salt.

Adelbert notes in his diary for November 20, 1684 that all prisoners captured in 1863 (as well as those who were sick) were to be exchanged. On November 22, 1864, Adelbert once again was brought to Savannah prior to entering a stockade in Florence, SC on November 27, 1864. On November 29, nine hundred prisoners came into camp, leading to a total of 11,000 prisoners in camp. However, 1,100 sick prisoners were taken out the day before. The weather was abnormally cold for that year and the prisoners had to build shanties (similar to Andersonville) to keep warm and dry.

It appears from his diary that he left Camp Florence on February 17, 1865 (although his diary mentions leaving Millen) with a final entry on February 20, 1865 in Wilmington, noting possible exchange. Military records show that Adelbert was paroled on February 27 or 28, 1865 in South Carolina and discharged May 2, 1865 in Maryland. He was a prisoner for about 270 days.

As noted above, Adelbert’s diary was lost around February 1865, but found by a fellow Andersonville prisoner from Illinois named Noah Potts (it did not appear that they knew each other), who used the diary on occasion (for minor personal entries) for almost two years until he sent the diary back to Adelbert (unsure how) with a brief note written in the diary to Adelbert dated November 15, 1867:

“Mr. Knight, I found this book at Willington, SC. Thought it might be of some use to you. Please write me a line when you receive this if you please. Noah Potts, Herman Knox Co., Ills.”

Adelbert returned to Lincolnville, Maine to work the family farm and marry Sarah Avesta Whitmore (a neighbor who wrote during his time in the service) in December 1865. He became a member of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) Post 42 in Belfast. His mother sold the farm in 1873, and purchased a house in Belfast (approximately 15 miles northeast of their Lincolnville farm) where Adelbert became a skilled craftsman. His mother passed away in 1886 and was buried with her husband and other children in Fletcher Cemetery in Lincolnville. Adelbert and Sarah had 5 children, one being my grandfather, Burt Leroy Knight. Adelbert passed away in 1913 and Sarah in 1916. Both are buried together in Grove Cemetery in Belfast with some of his children and grandchildren.